Minesweeper - a brief journey from JavaScript/React to Elm

10 November 2015

Tags: javascript react elm

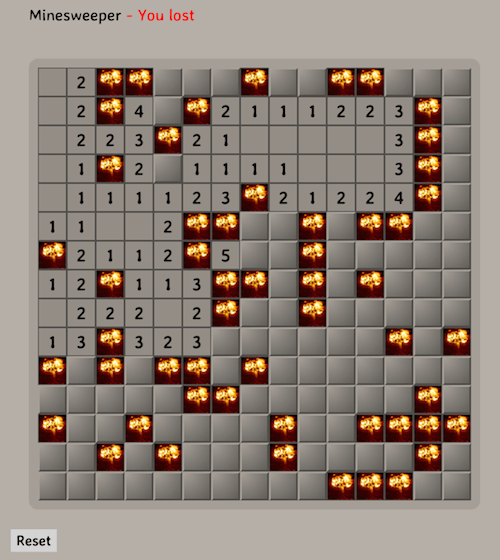

TweetAfter taking a keen interest to Elm lately I figured I needed to solve a real problem. Something a bit fun and achievable in a couple of evenings/nights. Not being awfully creative, piggiebacking on other peoples' work is sometimes a good option. In this post I’ll take you through some of my steps in porting/re-implementing https://github.com/cjohansen/react-sweeper (JavaScript and React) to an Elm implementation.

| If you’d like to have a look at the complete implementation of the game, check out https://github.com/rundis/elm-sweeper. There you’ll find instructions on how to get it running too. |

A little background

Right! So I’ve taken an interest in Elm lately. If you’ve read any of my previous posts you might have noticed that I’m quite fond of Clojure and ClojureScript. I still very much am and I have tons to learn there still. But I wanted to dip my toes into a statically typed functional language. Elm seems quite approachable and I guess probably the talk "Let’s be mainstream" made my mind up to give it a go. After creating a language plugin for Light Table: elm-light and attending an Elm workshop at CodeMesh, I needed something concrete to try it out on.

I remembered that a colleague of mine at Kodemaker, Christian Johansen, made a minesweeper implementation using JavaScript and React. That seemed like a sufficiently interesting problem and I could shamelessly steal most of the game logic :)

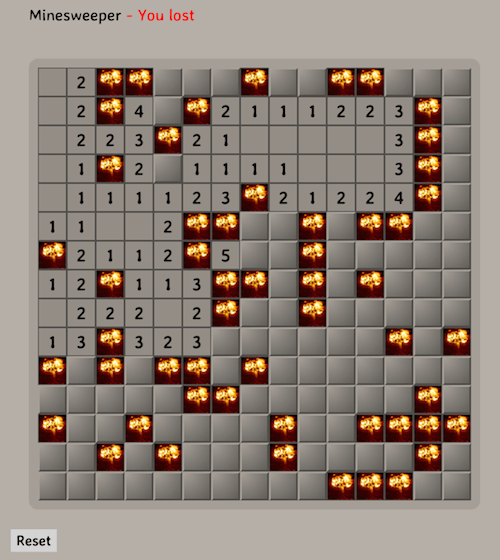

First steps - The Game Logic

So the obvious place to start was the game logic. I had the option of trying to set up Elm-Test to use a test-driven inspired approach. But heck I figured I had to try to put those types to the test, so I went for an all out repl driven approach. That gave me a chance to experience the good and bad with the repl integration of my own Light Table Elm plugin too.

Starting with records and type aliases

Reading the game logic in react-sweeper I decided to define a couple of types

type alias Tile (1)

{ id: Int

, threatCount: Maybe Int (2)

, isRevealed: Bool

, isMine: Bool}

type GameStatus = IN_PROGRESS | SAFE | DEAD

type alias Game = (3)

{ status: GameStatus (4)

, rows: Int

, cols: Int

, tiles: List Tile}| 1 | Type alias for records representing a tile in the game. |

| 2 | Threat count is a property on a tile that is not set until the game logic allows it. |

| 3 | Type alias for a record representing a game |

| 4 | Status of the game, the possible states are defined by GameStatus. SAFE means you’ve won, DEAD… well |

Describing these types proved to be valuable documentation as well as being very helpful when implementing the game logic later on.

What’s that Maybe thing ? If someone told me it’s a Monad I wouldn’t be any wiser. I think of it

as a handy way of describing that something may have a value. A nifty way to eliminate the use of null basically.

It also forces you to be explicit about handling the fact that it may not have a value.

You won’t get null pointer errors in an Elm program! (nor Undefined is not a function).

|

Finding neighbours of a tile

When revealing tiles in minesweeper you also reveal any adjacent tiles that aren’t next to a mine. In addition you display the threat count (how many mines are adjacent to a tile) for tiles next to those you just revealed. So we need a way to find the neighbouring tiles of a given tile.

JavaScript implementation

function onWEdge(game, tile) { (1)

return tile % game.get('cols') === 0;

}

function onEEdge(game, tile) { (2)

return tile % game.get('cols') === game.get('cols') - 1;

}

function nw(game, tile) { (3)

return onWEdge(game, tile) ? null : idx(game, tile - game.get('cols') - 1);

}

function n(game, tile) {

return idx(game, tile - game.get('cols'));

}

// etc , ommitted other directions for brevity

const directions = [nw, n, ne, e, se, s, sw, w];

function neighbours(game, tile) {

return keep(directions, function (dir) { (4)

return game.getIn(['tiles', dir(game, tile)]);

});

}| 1 | Helper function to determine if a given tile is on the west edge of the board |

| 2 | Helper function to determine if a given tile is on the east edge of the board |

| 3 | Returns the the tile north-west of a given tile. Null if none exists to the north-west |

| 4 | Keep is a helper function that maps over the collection and filters out any resulting `null`s. So the function iterates all directions (invoking their respective function) and returns all possible tiles neighbouring the given tile. |

Elm implementation

type Direction = W | NW | N | NE | E | SE | S | SW (1)

onWEdge : Game -> Tile -> Bool (2)

onWEdge game tile =

(tile.id % game.cols) == 0

onEEdge : Game -> Tile -> Bool

onEEdge game tile =

(tile.id % game.cols) == game.cols - 1

neighbourByDir : Game -> Maybe Tile -> Direction -> Maybe Tile (3)

neighbourByDir game tile dir =

let

tIdx = tileByIdx game (4)

isWOk t = not <| onWEdge game t (5)

isEOk t = not <| onEEdge game t

in

case (tile, dir) of (6)

(Nothing, _) -> Nothing (7)

(Just t, N) -> tIdx <| t.id - game.cols

(Just t, S) -> tIdx <| t.id + game.cols

(Just t, W) -> if isWOk t then tIdx <| t.id - 1 else Nothing

(Just t, NW) -> if isWOk t then tIdx <| t.id - game.cols - 1 else Nothing (8)

(Just t, SW) -> if isWOk t then tIdx <| t.id + game.cols - 1 else Nothing

(Just t, E) -> if isEOk t then tIdx <| t.id + 1 else Nothing

(Just t, NE) -> if isEOk t then tIdx <| t.id - game.cols + 1 else Nothing

(Just t, SE) -> if isEOk t then tIdx <| t.id + game.cols + 1 else Nothing

neighbours : Game -> Maybe Tile -> List Tile

neighbours game tile =

let

n = neighbourByDir game tile (9)

in

List.filterMap identity <| List.map n [W, NW, N, NE, E, SE, S, SW] (10)| 1 | A type (actually a tagged union) describing/enumerating the possible directions |

| 2 | Pretty much the same as it’s JavaScript counterpart. I’ve been lazy and assumed the id of a tile is also the index in the tiles list of our game. |

| 3 | Find a neighbour by a given direction. The function takes 3 arguments; a game record, a tile (that may or may not have a value) and a direction. It returns a tile (that may or may not have a value) |

| 4 | tileByIdx is a functions that finds a tile by its index. (it returns a tile, … maybe). tIdx is a local function that just curries(/binds/partially applies) the first parameter - game |

| 5 | A local function that checks if it’s okay to retrieve a westward tile for a given tile |

| 6 | Pattern match on tile and direction. You might consider it a switch statement on steroids. |

| 7 | If the tile doesn’t have a value (then we don’t care about the direction hence _) we return Nothing (Maybe.Nothing) |

| 8 | Just t, NW matches on a tile that has value (assigned t) and a given direction of NW. The logic is for this case the same as for it’s JavaScript counterpart. Well except it returns Nothing if NW isn’t possible |

| 9 | A partially applied version of neightBourByDir to make the mapping function in 10. a bit less verbose |

| 10 | We map over all directions finding their neighbours, then List.filterMap identity filters out all List entries with Nothing.

Leaving us with a list of valid neighbours for the given tile. |

We covered quite a bit of ground here. I could have implemented all the direction functions as in the JavaScript implementation, but opted for a more generic function using pattern matching. It’s not that I dislike short functions, quite the contrary but in this case it felt like a good match (no pun intended). Once you get used to the syntax it gives a really nice overview as well.

| Think of <| as one way to avoid parenthesis. It’s actually a backwards function application |

|

When testing this function I got my first runtime error in Elm complaining that my case wasn’t exhaustive. Rumors has it that the next version of elm might handle this at compile time as well :-)

|

Threat count

JavaScript

function getMineCount(game, tile) { (1)

var nbs = neighbours(game, tile);

return nbs.filter(prop('isMine')).length;

}

function addThreatCount(game, tile) { (2)

return game.setIn(['tiles', tile, 'threatCount'], getMineCount(game, tile));

}| 1 | Gets the number of neighbouring tiles that are mines for a given tile. (prop is a helper function for retrieving a named property on a js object) |

| 2 | Set the threatCount property on a given tile in the game |

Elm

mineCount : Game -> Maybe Tile -> Int (1)

mineCount game tile =

List.length <| List.filter .isMine <| neighbours game tile

revealThreatCount : Game -> Tile -> Tile (2)

revealThreatCount game tile =

{tile | threatCount <- Just (mineCount game <| Just tile)

, isRevealed <- True}| 1 | Same as for it’s JavaScript counterpart, but using a . syntax for dynamic property access |

| 2 | Almoust the same as addThreatCount, but since once we add it the tile would also always be revealed I opted for a two in one function. |

|

For mine count, both implementations are potentially flawed.

|

Revealing safe adjacent tiles

JavaScript

function revealAdjacentSafeTiles(game, tile) {

if (isMine(game, tile)) {

return game;

}

game = addThreatCount(game, tile).setIn(['tiles', tile, 'isRevealed'], true);

if (game.getIn(['tiles', tile, 'threatCount']) === 0) {

return keep(directions, function (dir) {

return dir(game, tile);

}).reduce(function (game, pos) {

return !game.getIn(['tiles', pos, 'isRevealed']) ?

revealAdjacentSafeTiles(game, pos) : game;

}, game);

}

return game;

}Elm

revealAdjacentSafeTiles : Game -> Int -> Game

revealAdjacentSafeTiles game tileId =

case tileByIdx game tileId of

Nothing -> game

Just t ->

if t.isMine then game else

let

updT = revealThreatCount game t

updG = {game | tiles <- updateIn tileId (\_ -> updT) game.tiles}

fn t g = if not t.isRevealed then revealAdjacentSafeTiles g t.id else g

in

if not (updT.threatCount == Just 0) then

updG

else

List.foldl fn updG <| neighbours updG <| Just updTA brief comparison

The most noteworthy difference is really the explicit handling of an illegal tile index in the Elm implementation. If I didn’t have the JavaScript code to look at, I’m guessing the difference would have been more noticable. Not necessarily for the better. We’ll never know.

Anyways, enough about the game logic. Let’s move on to the view part.

Comparing the view rendering

JavaScript

The React part for rendering the UI is found in ui.js Below I’ve picked out the most interesting parts

export function createUI(channel) { (1)

const Tile = createComponent((tile) => { (2)

if (tile.get('isRevealed')) {

return div({className: 'tile' + (tile.get('isMine') ? ' mine' : '')},

tile.get('threatCount') > 0 ? tile.get('threatCount') : '');

}

return div({

className: 'tile',

onClick: function () {

channel.emit('reveal', tile.get('id')); (3)

}

}, div({className: 'lid'}, ''));

});

const Row = createComponent((tiles) => {

return div({className: 'row'}, tiles.map(Tile).toJS());

});

const Board = createComponent((game) => {

return div({

className: 'board'

}, partition(game.get('cols'), game.get('tiles')).map(Row).toJS());

});

const UndoButton = createComponent(() => { (4)

return button({

onClick: channel.emit.bind(channel, 'undo')

}, 'Undo');

});

const Game = createComponent((game) => {

return div({}, [Board(game), UndoButton()]);

});

return (data, container) => { (5)

render(Game(data), container);

};

}| 1 | This function returns a function for creating the react component tree for the game. It takes a channel param, which is an event emitter. So when components need to notify the "controller" about user actions they can just emit messages to this channel A neat way to avoid using callbacks! |

| 2 | createComponent is a handy helper function that avoids some react boiler plate and provides an optimized shouldComponentUpdate function for each react component used. |

| 3 | When a user clicks on a tile a reveal message with the tile id is emitted |

| 4 | The game also supports undo previous move :) |

| 5 | Returns a function that when called starts the react rendering of the game in the given container element |

Elm

threatCount : Maybe Int -> List Html

threatCount count =

case count of

Nothing -> []

Just t -> [text (if t > 0 then toString t else "")]

tileView : Signal.Address Action -> Game.Tile -> Html (1)

tileView address tile =

if tile.isRevealed then

div [class ("tile" ++ (if tile.isMine then " mine" else ""))]

<| threatCount tile.threatCount

else

div [class "tile", onClick address (RevealTile tile.id)] (2)

[div [class "lid"] []] (3)

rowView : Signal.Address Action -> List Game.Tile -> Html

rowView address tiles =

div [class "row"] (List.map (tileView address) tiles)

statusView: Game -> Html

statusView game =

let

(status, c) = case game.status of

SAFE -> (" - You won", "status-won")

DEAD -> (" - You lost", "status-lost")

IN_PROGRESS -> ("", "")

in

span [class c] [text status]

view : Signal.Address Action -> Game -> Html (4)

view address game =

let

rows = Utils.partitionByN game.cols game.tiles

in

div [id "main"] [

h1 [] [text "Minesweeper", statusView game],

div [class "board"] (List.map (rowView address) rows),

div [] [button [class "button", onClick address NewGame] [text "New game"]]

]| 1 | The function responsible for rendering a single tile. Very much comparable to the React tile component in the JavaScript implementation. Similar to React, we aren’t returning actual dom elments, Elm also has a virtual dom implementation |

| 2 | When a tile is clicked a message is sent to a given address (we’ll get back to that a little bit later). Well actually it doesn’t happen right away, rather think of it as creating an envelope with content and a known address. The Elm runtime receives a signal back that will take care of sending the message to it’s rendering function when appropriate. |

| 3 | div here is actually a function from the HTML module in Elm. It takes two lists as arguments, the first is a list of attributes and the second is a list of child elements |

| 4 | Our main entry function for creating our view. It takes an address and game as parameter and returns a virtual dom node (Html) |

Signal.Address Action : Address points to a particular type of Signal, in our case the Signal is an Action

we’ll come back to that shortly. But the short story is that this is what enables us to talk back to the main application.

|

Wiring it all together

JavaScript

const channel = new EventEmitter();

const renderMinesweeper = createUI(channel);

let game = createGame({cols: 16, rows: 16, mines: 48});

let history = List([game]);

function render() { (1)

renderMinesweeper(game, document.getElementById('board'));

}

channel.on('undo', () => { (2)

if (history.size > 1) {

history = history.pop();

game = history.last();

render();

}

});

channel.on('reveal', (tile) => { (3)

if (isGameOver(game)) { return; }

const newGame = revealTile(game, tile);

if (newGame !== game) {

history = history.push(newGame);

game = newGame;

}

render();

if (isGameOver(game)) {

// Wait for the final render to complete before alerting the user

setTimeout(() => { alert('GAME OVER!'); }, 50);

}

});| 1 | The react render entry point for the game. Called whenever the game state is changed |

| 2 | The JavaScript implementation keeps a history of all game states. I forgot to mention that immutable-js is for collections. Undo just gets the previous game state and rerenders. Nice and simple |

| 3 | Event listener for reveal messages. It invokes reveal tile, adds to history (and potentially ends the game). |

This is all very neat and tidy and works so great because the game state is managed in one place and is passed through the ui component tree as an immutable value. The fact that the state is immutable also makes the undo implementation a breeze. I really like this approach !

Elm

If you don’t know Elm at all, this part might be the most tricky to grasp. To simplify things I’ll split it into two parts.

Start-app approach

Start-app is a small elm package that makes it easy to get started with an elm Model-View-Update structure. This is a great place to start for your first elm app.

type Action = RevealTile Int (1)

init : Game (2)

init =

Game.createGame 15 15 5787345

update : Action -> Game -> Game (3)

update Action game =

case action of

RevealTile id -> if not (game.status == IN_PROGRESS) then game else (4)

Game.revealTile game id

main = (5)

StartApp.Simple.start (6)

{ model = init

, update = update

, view = view

}| 1 | Type describing the actions the game supports. Currently just revealing tiles, and you can see that we also specify that the RevealTile action expects an Int paramater. That would be the tile id. |

| 2 | The init function provides the initial state for our application. createGame is a helper function for creating

a game with x cols and y rows. The 3.rd param is a seed for randomizing tiles. We’ll return to that seed thing in the next chapter! |

| 3 | Update is the function that handles the actual update of state, or rather the transformation to the next state based on some action. It’s quite simple in this case, just reveal a given tile and return the updated game |

| 4 | No point in revealing more tiles when the game is already over :) |

| 5 | main is the entry point into our application. If you use elm-reactor this will be automatically invoked for you, which is handy for getting started quickly |

| 6 | StartApp.Simple.start takes care of wiring things up and start your application |

Trouble in paradise, we get the same board every time

Do you remember the 3rd param to createGame in the previous chapter? That is the initial seed to a random generator (Random) to randomize the occurence of mines. The problem is that using the same seed produces the same result. Calling an elm random generator will return a new seed, so of course I could/should have stored that and used that for the next game. But I still need an initial seed that’s different every time I start the app. Current time would be a good candidate for an initial seed. But there is no getCurrentTime function in Elm. Why ? It’s impure, and Elm doesn’t like impure functions. By "pure", we mean that if you call a function with the same arguments, you get the same result. There are several reasons why pure functions is a great thing (testing is one), but I won’t go into that, let’s just accept the fact that this is the case, so how can we deal with it ?

Well the elm-core package has a Time module with a timestamp function that looks useful. To use that we have to change a few things though, most notably we can’t use the simple start app approach any more.

type Action =

NewGame (1)

| RevealTile Int

update : (Float, Action) -> Game -> Game (2)

update (time, action) game =

case action of

NewGame -> Game.createGame 15 15 (truncate time) (3)

RevealTile id -> if not (game.status == IN_PROGRESS) then game else

Game.revealTile game id

actions: Signal.Mailbox Action (4)

actions =

Signal.mailbox NewGame

model: Signal Game (5)

model =

Signal.foldp update init (Time.timestamp actions.signal)

main : Signal Html (6)

main =

Signal.map (view actions.address) model

port initGame : Task.Task x () (7)

port initGame =

Signal.send actions.address NewGame| 1 | We introduce a new action NewGame |

| 2 | Our update function now takes a tuple of time and action + game as input parameters |

| 3 | We use the elm core function truncate to convert the time(stamp) float into an integer and use that as our seed to createGame |

| 4 | We construct a mailbox for our Action messages manually, with an initial value of NewGame |

| 5 | Our model is a fold (reduce) of all state changes sent to our mailbox (from the app started to the current moment of time). This is where we introduce the Time.timestamp function, which wraps our action signal and produces a tuple of (timestamp, action) |

| 6 | main is just a map over our view function with our current model. Since view also expects an (mailbox) address we curry/partially apply that to our view function |

| 7 | Unfortunately I couldn’t figure out how to get the timestamp passed to the init function. The creation step (4) of the mailbox doesn’t actually cause the NewGame action to be executed either. So this is a little hack that fires off a task to execute the NewGame action. This is run after initialization so when you load the game you’ll not see state 0 for the game, but actually state 1. If any elm-ers out there reads this, feel free to comment on how this could be done in a more idiomatic fashion! |

| I found this blogpost very illuminating for deconstructing start-app. |

But what about undo ?

There is an elm-package I think would help us do that quite simply; elm-undo-redo. However if you are using elm-reactor you pretty much get undo-redo and more out of the box. Great for development, but maybe not so much for production!

Summary

Getting into Elm has been a really pleasurable experience so far. It’s quite easy to get up and running without knowing all that much about the language. I’ve found the elm compiler to be a really nice and friendly companion. The error messages I get are really impressive and I can truly say I’ve never experienced anything quite like it. Working with types (at least for this simple application) hasn’t felt like a burden at all. I still feel I should have had some tests, but I think I would feel more comfortable refactoring this app with a lot less tests than I would in say JavaScript.

If my intention for this post had been to bash JavaScript I chose a poor example to compare with. But then again that was never my intention. I wanted to show how a well written JavaScript app might compare to an Elm implementation written by an Elm noob. Hopefully I’ve also managed to demonstrate that it’s not all that difficult getting started with Elm and perhaps peeked your interest enough to give it a try !

Resources

These are some of the resources that have helped me getting up to speed:

-

Elm: Building Reactive Web Apps - A really nice step-by-step tutorial with videos and examples to get you up to speed. You get great value for $29 I think.

-

Elm: Signals, Mailboxes & Ports - Elm signals in depth. Really useful for getting into more detail on what Signals are, how they work and how to use them.

-

Elm Architecture Tutorial - Tutorial outlining "the Elm Architecture"

-

elm-lang.org - The official site for the elm language

-

elm-light - My elm plugin for Light Table, or if you use another editor it might be listed here

Addendum - Potential improvements

-

Initialize game with seed without adding an extra state

-

Perhaps I should/could have used extensible records to model the game

-

Maybe Array would be a better choice than List for holding tiles ?